Reverse Engineering a Thermal Label Printer

Table of Contents

- State of the Art of Thermal Printers

- Introduction to The Egg

- Commanding The Egg

- The Egg Does Not Support ESC/POS (mostly)

- Egg Conclusion

Last week while I was out shopping, I found a little sort-of-egg-shaped thermal label printer. I didn’t really need (another) label printer but I got it because the box said it supported Bluetooth and I really wanted to know how the “official app” communicated with it. I spent the next three days going down a rabbit hole of learning very specific information about thermal printers, and discovered that the printer I had bought was both very similar and very different to existing thermal printers!

Through my research I learned a lot about how many modern thermal printers are communicated with: a standard command set called ESC/POS. The first section of this post is really just a summary of what I’ve found about the state of the art. The remaining sections are discussions on the various features of the label printer I bought. There are a lot of interesting design choices that went into this product, and I have some ideas as to why those decisions were made.

I don’t think this knowledge is particularly useful outside of a few specific applications but I hope you find it interesting anyway! This post roughly follows the approach I used when researching this device, and as such it reads a bit like a story. If you’re only interested in the technical information about the printer, I’ve collated all the results of my reverse engineering in this summary. If you decide to read on, I hope you find it entertaining!

State of the Art of Thermal Printers

The majority of thermal devices you see in the wild connect to a host device using RS-232 / Serial or USB. A lot of these printers are integrated into larger appliances (eg: receipt printer in a POS system) although it’s very common to find a standalone printer which provides a Bluetooth or Wifi interface. Many thermal printers, even newer ones, can be controlled using a command set called ESC/POS. This began as a control language for non-thermal Epson printers called ESC/P, and was eventually adapted into a language for interfacing with thermal printers.

ESC/POS is very heavily based in ASCII. Regular text is represented as plain ASCII, and formatting and other functions are implemented using ASCII control codes. Control commands are escaped using the Escape character (0x1b), the Group Separator character (0x1d), or the Data Link Escape character (0x10). For example, to enable emphasis mode (which makes the text a little bolder) you would send ESC E n (1B 45 n in hex) to the printer using whichever communication protocol it supports, where n=1 to enable emphasis or 0 to disable it. Commands exist to set text emphasis, underlining, strikethrough, alignment, as well as other features like font selection. ASCII formatting characters like horizontal tab and carriage return are supported as well.

Additional commands exist for printing graphics. There is a command which can be used to print a bitmap / raster image, as well as support for generating and printing different types of barcode. Along with standard ASCII control codes like form feed, there are dedicated commands for feeding the paper by a certain amount, and even cutting the paper if the printer supports it. There are many, many, many more ESC/POS commands for doing very specific things, so check it out if you would like to fall down that rabbit hole. Sadly, a lot of ESC/POS commands can’t be used with the printer I’ll be discussing in the rest of this post…

Introduction to The Egg

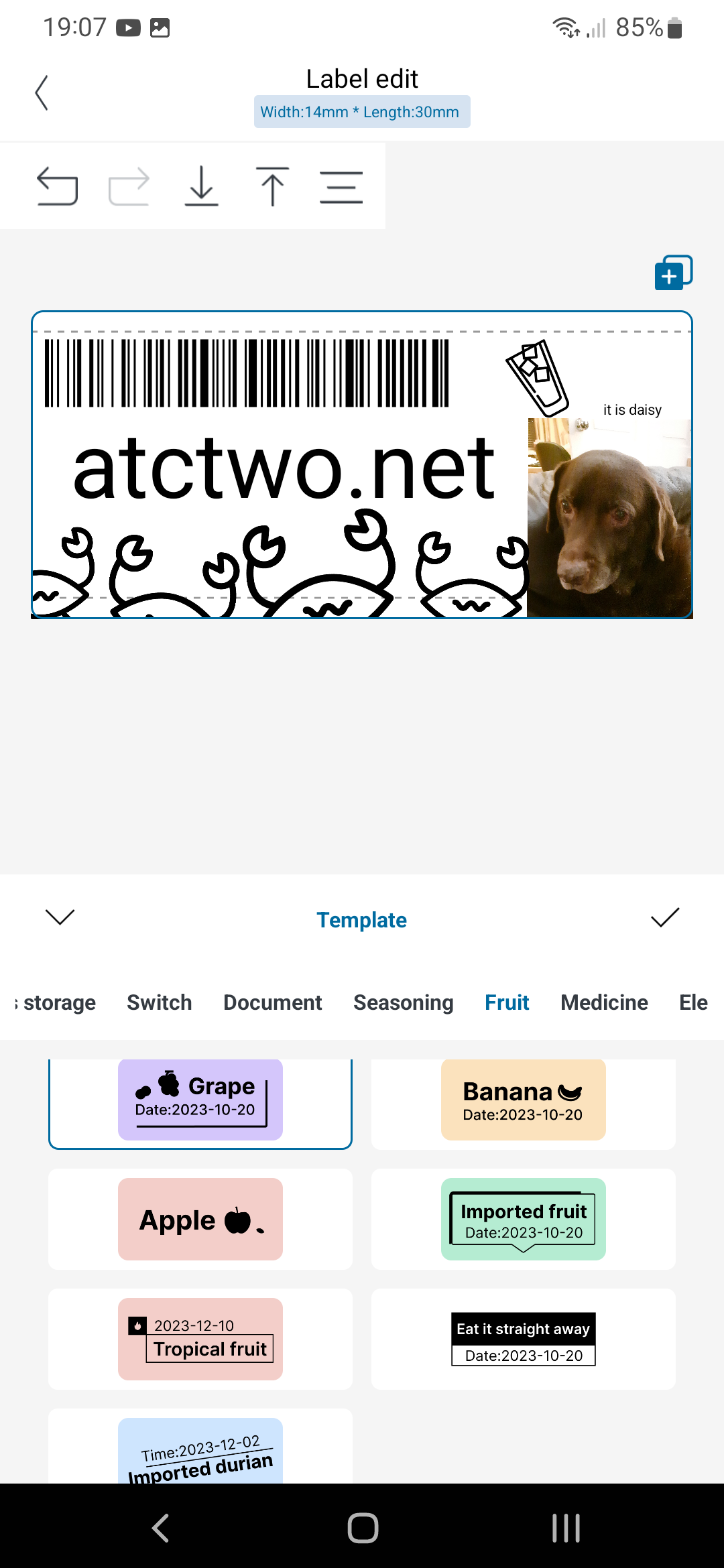

Before diving into the technical details of how it works, I want to discuss the printer itself for a bit. I purchased it at a Lidl in Belfast, Northern Ireland, because I thought it would be fun to reverse engineer it (i was right). On the box it claims that to use it, you connect your Android or iOS device to it via Bluetooth. It has a 18500 Li-Ion battery (1200 mAh), and a USB-C port for charging (5V DC, 1A). It came with one roll of 14mm x 30mm labels (most of which have been wasted during testing).

(I wasn’t able to find a product page for the printer on Lidl NI’s website, so here’s one for Lidl Ireland. In case they remove the product page once they stop selling it I archived the page on the Wayback Machine and archive.ph.)

This printer prints onto individual self-adhesive labels, rather than onto a roll of thermal paper. It has a little infra-red reflective sensor on the inside to detect when it’s run out of paper. During testing I cut a long strip of regular thermal paper and rolled it up, and the Egg was able to print on it with no issues.

Pocket Printer

The box has a QR code which links to this page, which then redirects to either the App Store or Google Play Store page for the official app, called “Pocket Printer” (unrelated to the Game Boy Printer). The app has a pretty decent label editor with a number of included templates for various household items like medicine or documents. It also allows you to see your printer’s battery level, firmware version, serial number, and MAC address. You can set a default print density (ie: how “intense” the dots on the prints are), as well as a timeout for the automatic shutdown feature.

Who Made It?

The printer is being sold under the “Silvercrest” brand, which I think Lidl uses mostly for selling white label electronic appliances. Looking at the box and the included user manual, we can see that the printers are actually being distributed by a company called Karsten International. Karsten are a company which provide white label goods to other companies to sell under their own brands. They actually have a really interesting range of generically branded thingies for many different applications.

Looking at the app store pages for the Pocket Printer app, we can see that Karsten is the app’s publisher. Interestingly the Android app’s package name is com.printer.lidloffice, suggesting that this app was distributed on behalf of Lidl. It implies that Lidl are the only company that have resold this printer from Karsten, but this isn’t actually true. Karsten have also published a very similar app called Fichero Printer (App Store, Google Play Store) for use with the same model of printer, being sold under the “Fichero” brand.

(Another thing of interest is that Pocket Printer claims to be version 1.2.8, while Fichero Printer claims to be version 1.0.3!)

Even though Karsten distributed the printer, that doesn’t mean they manufactured it. The device’s Bluetooth name suggests that the printer’s actual, original model name is L13. Searching for “l13 thermal printer”, I found the device being sold with no branding on sites like Amazon. I found a website containing data from the OEM’s user manual, along with the device’s FCC ID! Looking at the device’s FCC information I discovered that the OEM was a company called Xiamen Print Future Technology Co., Ltd.

This isn’t super useful information but I thought it was interesting!

Commanding The Egg

After gathering information on the origins of the printer, I started trying to figure out how the Pocket Printer app sent data to the printer. The only details provided on the box was that it uses “Bluetooth”, and I assumed this to mean Bluetooth Low Energy for some reason. (I was right, but that wasn’t the whole story.) I used nRF Connect to enumerate the BLE services that the device implemented. I’ll include full details of the services and their characteristics in the reverse engineering document, but for this post it’s enough to say that there were four different custom services. I had no idea what any of them did so I started searching the internet for the services’ UUIDs.

The first UUID I got any concrete information on was 49535343-fe7d-4ae5-8fa9-9fafd205e455, which is sort of standardised by Microchip as a de facto UART service called Transparent UART. Commands are sent to the printer using it’s RX characteristic, and responses to commands that produce them are transmitted using the TX characteristic.

The UUID e7810a71-73ae-499d-8c15-faa9aef0c3f2 led me to find a few GitHub issues and StackOverflow posts about using Bluetooth thermal printers. Further research along this path led me to discover ESC/POS in the first place. At this point I guessed that each of the Bluetooth printers in these posts, as well as my Egg, could be running related firmware. From this I made the (mostly wrong) deduction that my Egg Printer supported ESC/POS, however learning about ESC/POS and how other thermal printers worked (Bluetooth or otherwise) really helped me figure out how this printer functions.

I initially assumed that each UUID implemented a different function (eg: one was for ESC/POS, one was for battery level, etc). I later realised that each UUID did exactly the same thing. They were all basically UART services! All the printing commands, as well as the commands like getting the battery level and firmware version, were done via the same serial interface that could be accessed from any of the four services. I don’t have any proof of why the developers might have done this, but my guess is that it was for compatibility reasons. When I was researching the BLE UUIDs I found that there were a lot of different printers that supported BLE, and I’m guessing they all used different service UUIDs from each other. I think the firmware developers decided to support multiple commonly used services so that developers of the client software could reuse old code, or that end users could use existing software.

When I was still trying to figure out what each BLE service was for, I decided to use my phone to sniff the Bluetooth HCI activity so I could export it to my computer and inspect the traffic using Wireshark. This method meant that I could see exactly which BLE services the official app was using for which purpose. Of course, my assumptions were mostly wrong since I discovered that Pocket Printer doesn’t actually use BLE at all. It connects to the printer using classic Bluetooth’s Serial Port Profile. All the communication between the client and the printer were done over SPP. There aren’t really differences in usage between SPP and any of the printer’s BLE services, but I was still really surprised at this. This lends further credibility to my compatibility theory.

Also lending credibility to my compatibility theory is the fact that it can communicate over USB! It sadly doesn’t show up as a virtual serial port, but it does show up as a USB printer device, with the same endpoints that many common USB thermal printers use. I was able to use the printer with python-escpos over USB mode (within the limits of the printer discussed in the next section). While the USB-C port is mentioned in the manual as a means to charge the internal battery, it doesn’t make any mention of it being usable for communicating with the printer. However there are likely very few applications that would fully support this printer other than the official app, due to its non-standard command set.

The Egg Does Not Support ESC/POS (mostly)

For most of my early testing I used python-escpos to communicate with the printer, and I found that most ESC/POS commands didn’t work, except for the following three:

- the raster image command (

GS V 0;1D 76 30) - print and feed paper (

ESC J n;1B 4A n) - form feed (

FF;0C)

I was working under the assumption that the printer supported a subset of ESC/POS, but later I realised that it was probably more accurate to say that these commands are the only ones that resemble any from ESC/POS. All of the printer’s other commands (derived from snooping traffic from the app) were completely custom, as far as I could see.

The L13 will only print something if it’s been sent as a raster image. It doesn’t support plain ASCII like ESC/POS printers do. Since the width of the thermal element in the printer is only as wide as a label (14mm) it makes sense that it doesn’t support printing text. For text to be printed along the length of the label rather than along the width, it would need to be rotated by 90° anyway, so I think the developers just expected any client software to mostly be dealing with raster images anyway. Despite most of the rest of the L13’s command set being propriety, the raster image command seems to function exactly as the ESC/POS standard defines it, with all the same parameters.

Also supported are the print and feed paper command, and the form feed command. The form feed command (0x0c) is defined in ASCII so it could be argued that this isn’t specifically an ESC/POS command. I spent a while trying to figure out how the printer can be instructed to line up the next label for printing, since FF on it’s own seems to just go forward by one label exactly, irrespective of the position of the current label. The Bluetooth log shows that this sequence is used by the app:

| Step | Command Bytes | Function |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 0C |

form feed |

| 2 | 1B 4A 28 |

print and feed paper |

I still don’t really know why this combination of commands works, but it’s a useful sequence to know!

Custom Commands

The Bluetooth log shows that Pocket Printer issues a number of propriety commands. I haven’t been able to find any reference of these commands being used by other printers, and while it is possible that there are other printers that implement these commands, their existence makes it a little less likely that the Egg is running related firmware to other printers.

These are the commands that I’ve been able to discover, and what I think each of them do:

| Command Bytes | Function | Notes |

|---|---|---|

10 FF 20 F0 |

returns model number | my printer returns DP-L13 |

10 FF 20 F1 |

returns firmware version | my printer returns V3.05 |

10 FF 20 F2 |

returns serial number | my printer returns L1324144345 |

10 FF 50 F1 |

returns battery level | the least significant byte is the charge level in percent (eg: 00 5C means 92%) |

10 FF 40 |

returns paper status | returns 0x00 if there is paper and 0x04 if there is no paper |

10 FF 10 00 n |

set print density | where n = 0x00 for light, 0x01 for medium, 0x02 for thick |

10 FF 12 00 n |

set auto-shutdown timeout | where n is the timeout in minutes the official app supports 5, 10, 20, 30, 60 |

10 FF F1 30 and 12x00s |

??? | sent before sending image command |

10 FF F1 45 |

??? | sent after sending image command |

10 FF 13 |

??? | responded 0x14 in my testing |

10 FF 11 |

??? | responded 0x01 0x0a 0x01 in my testing |

I’m not sure what the last four commands are, and I haven’t checked if their responses change over time. Additionally, 0x10 is a valid escape character in ESC/POS (called Data Link Escape, or DLE), but there aren’t any ESC/POS commands that I can see that start 10 FF. I don’t really have any speculation as to why these bytes were used for these commands since I can’t find anything else that implements them. For now, it remains a mystery…

Print Sequence

The most practical thing I derived from the Bluetooth log was a complete sequence of commands for printing. This sequence includes all the initialisation, printing, paper feeding, and mystery commands that the Pocket Printer app sends when you press Print.

1. Check if there's paper - 10 FF 40

The printer uses an internal IR sensor to detect if there's paper loaded.

2. If there is paper, send ??? - 10 FF F1 03 followed by 12 00s

As mentioned in the last section I have no idea what this does :P. However, in my testing I discovered that this procedure still works without this command...

3. Print Raster Image - 1D 76 30 00 0C 00 F0 00 followed by image data

The explanation for this command requires a bit of info about the ESC/POS raster image command. The command's signature is 1D 76 30 m xL xH yL yH <data>. m specifies the "print mode" and in this case this is set to normal. The tricky parts are the last four bytes, which basically specify the width and height of the image. xL and xH specify the number of bytes per horizontal row, while yL and yH specify the number of vertical dots (ie: the number of rows). They are expressed using a formula but if you want more info about this, check out the official reference for this command.

In the commands sent by Pocket Printer, the values for the image height are set for the expected label length of 30mm. At 203 DPI, that works out at ~240 pixels, which according to the ESC/POS command reference results in the last two bytes of the command before image data being F0 00. If you were to use 40mm labels (which some other printers use), at 203 DPI that would work out at ~320px, which would mean the last two bytes should be 40 01!

According to bytes 5 and 6 of the command, Pocket Printer sends 12 bytes per row. Since the images are effectively 1-bit colour (either the heater for each dot is on or it isn't), that means there's 8 pixels per byte. At 12 bytes per row, that works out at the width for each image being 96px.

4. Form Feed - 10 0C

This command moves the paper along a little bit, but not to the next label. I don't know why it sends 10 0C, since 0C works fine on it's own. Interestingly, the printer actually responds to this command with OK.

5. Print and Feed - 1B 4A 28

The other supported ESC/POS command, this will feed the paper by 0x28 units, which is enough to line up the next label. If you were using 40mm paper it's possible that this number would need to be changed.

6. Send ??? - 10 FF F1 45

This is the other command which I have no idea about the purpose of. The print seems to work fine without this command too.

That’s the command sequence derived from the Bluetooth log! It’s interesting that the app doesn’t perform the form feed commands before printing, only after. If you print something with the label halfway past the thermal element it will just start printing in the middle of the label.

Egg Conclusion

So, that’s all I’ve discovered about this printer! I hope you enjoyed this infodump about thermal printers in general. Since this printer seems to be somewhat obscure, I hope that this post provides a little bit of info about how it (or similar printers) work, and that it might help someone with this printer extend what they’re able to do with it. I’ve really wanted to do a thermal printer project for a while but I haven’t had any ideas, so this felt like a good introductory project! Although I think using a more standard thermal printer would have been easier…

Sources

This project was mostly research, so I want to leave you with a list of all the places I discovered this stuff from!

ESC/POS

- This introduction to ESC/POS by mike42

- the python-escpos library, both using the library and analysing it’s source code

- official ESC/POS command reference by Epson

- documentation on the commands supported by printers made by Pyramid Technologies

- this Python script for controlling another printer (Phomemo D30) (this helped me understand the size parameters for the raster print command) by polskafan

- this package for using various Phomemo printers (the readme has lots of details on command headers) by vivier

BLE Services

- the Thermal_Printer Arduino library by bitbank_2

- this Thermal_Printer GitHub issue regarding adding support for a cat-shaped printer

- this article about BLE services for another thermal printer (PT-210) by citrusdev