C++'s std::map and using strings as keys

Table of Contents

Recently, I was working on some C++ code, using std::maps to map setting names (as strings) to their configured values (also as strings). Initially, all the key names were either specified using string literals, or variables assigned to literals, and it worked fine. Then I tried to access mappings using strings loaded from a drive at runtime as keys, but it was accessing different values than expected. This post will explain what happened, and how to resolve it!

This post assumes knowledge of the basics of C++, and a little about program compilation.

std::map basics

This section will include a brief overview of how std::maps work. If you already know how they work you can probably skip this section.

std::maps are C++’s standard associative array data type (actually they are implemented as classes). They are functionally the same as Python’s dictionaries, JavaScript’s objects, Java’s HashMaps, and so on. They relate pairs of values - a key and a value. The key is used as an index, with which the value is accessed.

For example:

#include <iostream>

#include <map>

int main()

{

// initialise map - initially it has no mappings

// since C++ is statically typed you have to specify the data type of both the keys and the values

std::map<int, int> scores;

// add mappings to relate a player ID to their score

scores[0] = 496;

scores[1] = 253;

scores[2] = 548;

scores[3] = 903;

scores[4] = 246;

// print the score for each player

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++)

{

std::cout << "Score for player " << i << ": " << scores[i] << std::endl;

}

}

Outputs:

Score for player 0: 496

Score for player 1: 253

Score for player 2: 548

Score for player 3: 903

Score for player 4: 246

The example above kind of makes it look like an array, but the values of keys don’t have to be consecutive. For example:

// initialise map - initially it has no mappings

std::map<int, int> scores;

// add mappings to relate a player ID to their score

scores[20] = 496;

scores[50] = 253;

scores[40] = 548;

scores[10] = 903;

scores[30] = 246;

// since the keys aren't in the range 0..4, we have to iterate over the map differently.

// this use of the enhanced for loop gives each iteration access to a `std::pair`,

// which can be used to access both the key and value of a mapping.

for (std::pair<int, int> mapping : scores)

{

std::cout << "Score for player " << mapping.first << ": " << mapping.second << std::endl;

}

Output:

Score for player 10: 903

Score for player 20: 496

Score for player 30: 246

Score for player 40: 548

Score for player 50: 253

In fact, keys don’t even have to be ints. Any data type can be used. Here’s an example using const char* keys:

// initialise map - initially it has no mappings

std::map<const char*, int> scores;

// add mappings to relate a player name to their score

scores["Alice"] = 496;

scores["Bob"] = 253;

scores["Ruby"] = 548;

scores["Riley"] = 903;

scores["Eve"] = 246;

// since the keys aren't in the range 0..4, we have to iterate over the map differently.

// this use of the enhanced for loop gives each iteration access to a `std::pair`,

// which can be used to access both the key and value of a mapping.

for (std::pair<const char*, int> mapping : scores)

{

std::cout << "Score for " << mapping.first << ": " << mapping.second << std::endl;

}

Output:

Score for player Riley: 903

Score for player Ruby: 548

Score for player Eve: 246

Score for player Alice: 496

Score for player Bob: 253

However, there is a possible problem with using things other than ints, and this is the problem I had when using const char*s as keys.

The Problem

In my original code, I was keeping track of user settings using a std::map<const char*, const char*>. The key would be the name of a setting, and the value would be whatever the setting was set to by the user. A simplified version is shown below:

std::map<const char*, const char*> settings;

settings["NTP Server"] = "pool.ntp.org";

settings["GMT Offset"] = "0";

settings["Minimum Brightness"] = "16";

settings["Maximum Brightness"] = "120";

settings["Rainbow Speed"] = "14000";

settings["OpenWeatherMap API Key"] = "<whatever my key was>";

At the start of development, any time I accessed a mapping, I would use either a string literal, or a variable assigned to a literal.

printf("%s", settings["NTP Server"]);

void set_setting(const char* setting_name, const char *setting_value)

{

settings[setting_name] = setting_value;

}

set_setting("Rainbow Speed", "10000");

const char *get_setting(const char* setting_name)

{

return settings[setting_name];

}

This worked absolutely fine, until I started using key strings loaded at runtime. I was trying to implement a system which would load configuration values from a file on an SD card, and then populate the settings map with them. The file would be a JSON file, with a direct mapping of key to value to be loaded into settings. I found that accessing a mapping using a string literal yielded a different mapping than when using a string loaded at runtime.

For the example below, I decided not to use any file access functions, since the same effect can be acheived by “assembling” a new string at runtime.

std::map<const char*, const char*> settings;

char key_name_literal[100] = "Rainbow Speed";

settings[key_name_literal] = "14000";

printf("%s\n", settings[key_name_literal]);

// this will print "14000"

char key_name_runtime[100] = "Rainbow";

strcat(key_name_runtime, " Speed"); // this will concatenate " Speed" on to the end of "Rainbow"

printf("%s\n", settings[key_name_runtime]);

// this will print "(null)"

The Explanation

Since this is C++, the reason this is happening is because pointers. We have to first talk a bit about how std::map actually works.

In order to relate a key to a value, the key is hashed - processed into a numerical value. This value is ultimately used as some index or address-type-thing, which is used to locate the location in memory of the value that they key points to. When you use an int as the key, the number is transformed into another number. One of the key properties of the hashing algorithm is that the values it produces must be unique (or close to it), meaning that each value of the key type doesn’t conflict with another for value space.

I had assumed that when you use a string as a key, it generates an index based on each of the characters in the string - that way, each string produces a unique value. But as it turns out, when you use a const char*, the std::map will just see it as a single number - remember that const char*s are basically just pointers to a location in memory where each character of a string is stored consecutively. A variable of type const char*, even though we say it’s a string, it really just a pointer to a string (hence the *).

The effect of this is that, given two const char*s with the same contents, but at two different locations in memory, std::map will treat them as two entirely different strings, and therefore will map them to two different values!

To demonstrate how compile-time and runtime strings can be technically different despite their contents, I used Compiler Explorer to show what the compiler generates for these two types of string. The compiler I’m using is x86-64 gcc 9.1 (parameters are -m32 -mregparm=2). If you don’t really want to know the technical details, you can skip to the next section.

#include <string.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

const char *key_name_literal = "Rainbow Speed";

}.LC0:

.string "Rainbow Speed"

main:

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

sub esp, 16

mov DWORD PTR [ebp-4], OFFSET FLAT:.LC0

mov eax, 0

leave

retIn this first assembly code block, you can outright see the string “Rainbow Speed” stored verbatim in the .LC0 section of the binary. In the main section, all it’s doing is setting up the main() function, and moving the address of the string into a byte on the stack (ebp-4).

#include <string.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

char key_name_runtime[14] = "Rainbow";

strcat(key_name_runtime, " Speed");

// this will concatenate " Speed"

// on to the end of "Rainbow"

}main:

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

push edi

sub esp, 16

mov DWORD PTR [ebp-18], 1852399954

mov DWORD PTR [ebp-14], 7827298

mov DWORD PTR [ebp-10], 0

mov WORD PTR [ebp-6], 0

lea eax, [ebp-18]

mov ecx, -1

mov edx, eax

mov eax, 0

mov edi, edx

repnz scasb

mov eax, ecx

not eax

lea edx, [eax-1]

lea eax, [ebp-18]

add eax, edx

mov DWORD PTR [eax], 1701860128

mov WORD PTR [eax+4], 25701

mov BYTE PTR [eax+6], 0

mov eax, 0

add esp, 16

pop edi

pop ebp

retIn the second assembly block, the code first places the word “Rainbow” onto the stack. It then places the string “ Speed” in the stack, right after “Rainbow” ended. The code is doing a series of other things in between these two actions but I don’t really know what they are!

#include <string.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

const char *key_name_literal = "Rainbow Speed";

char key_name_runtime[14] = "Rainbow";

strcat(key_name_runtime, " Speed");

}.LC0:

.string "Rainbow Speed"

main:

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

push edi

sub esp, 32

mov DWORD PTR [ebp-8], OFFSET FLAT:.LC0

mov DWORD PTR [ebp-22], 1852399954

mov DWORD PTR [ebp-18], 7827298

mov DWORD PTR [ebp-14], 0

mov WORD PTR [ebp-10], 0

lea eax, [ebp-22]

mov ecx, -1

mov edx, eax

mov eax, 0

mov edi, edx

repnz scasb

mov eax, ecx

not eax

lea edx, [eax-1]

lea eax, [ebp-22]

add eax, edx

mov DWORD PTR [eax], 1701860128

mov WORD PTR [eax+4], 25701

mov BYTE PTR [eax+6], 0

mov eax, 0

add esp, 32

pop edi

pop ebp

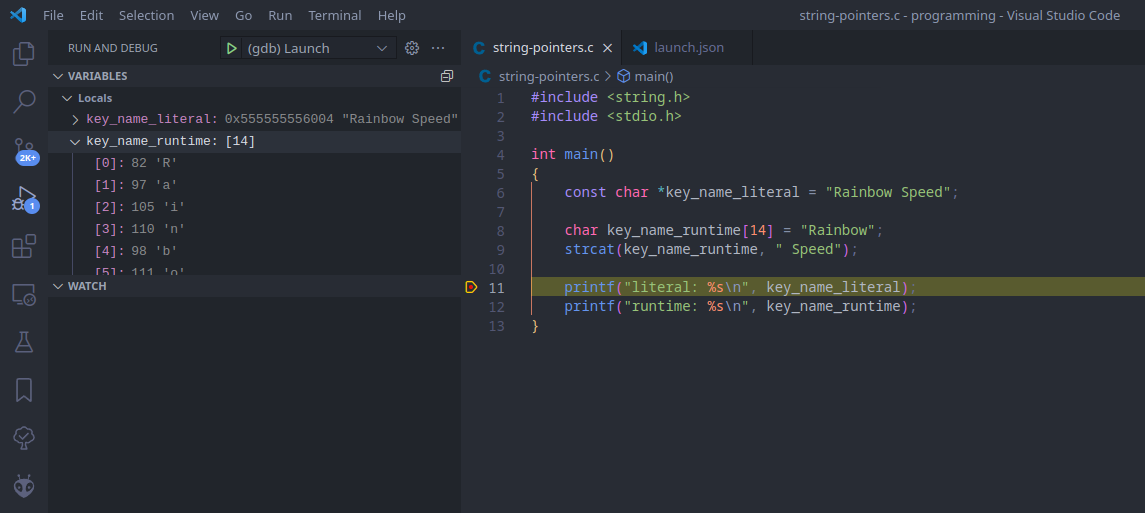

retYou can see that when both types of string are present in the code, both string techniques are used by the compiler. Critically, you might observe that the two strings are stored at different positions in the stack. The variable key_name_literal is stored at ebp-8 and points to data in .LC0, while key_name_runtime is at ebp-20 and points to data in main()’s stack frame. This is demonstrated in this screenshot of me debugging the code in VS Code, where you can see the contents of the two variables in the pane on the left:

After playing around with a combination of const char*, const char var[100], and char var[100], I think the thing that decides which string technique the compiler uses is whether the string’s size is specified at runtime. const char* produced the result seen in the first assembly code block, while const char var[100] and char var[100] produced what was seen in the second code block. I would have assumed that it would be the presence of const that would determine that.

If you find this really interesting, here is a paper by Chae Jubb that goes into more rigorous depth about how gcc handles string compilation at various optimisation levels.

Workarounds

There are a couple of ways you could get around this issue. I’m going to talk about three ideas I had, but there are probably ways to get around this issue I hadn’t thought of.

Match keys with linear search

The first workaround I thought of using was using some type of linear search to find an existing key-value pair with the same key contents. Instead of using a string as a key directly, I would use this match function to first find a key with the same contents. If there is a match, the function returns a pointer to the string used as the key, which can then be used directly with the map - this works because the same pointer will be returned every time for any given string of characters. If there isn’t a match then it just returns the input string.

Here’s an example of how this would be implemented:

#include <iostream>

#include <map>

#include <string>

template <typename K, typename V, typename T>

K match_key(std::map<K, V> m, T *target_key)

{

// check each key in the map

for (auto it = m.begin(); it != m.end(); ++it)

{

// if the target key is actually the same pointer as the key

if (it->first == target_key) return it->first;

// if the key has the same contents as the target

if (strcmp(it->first, target_key) == 0)

{

// return the key (a pointer to a string with the key's name)

return it->first;

}

}

// if we reach this point, the target has no matching key in the map

// so make one!

return target_key;

}

int main()

{

// create settings map

std::map<const char*, const char*> settings;

// set value via literal

char key_name_literal[100] = "Rainbow Speed";

const char *matched_key_literal = match_key(settings, key_name_literal);

settings[matched_key_literal] = "14000";

// get value via literal

printf("%s\n", settings[matched_key_literal]);

// this will print "14000"

// determine runtime string

char key_name_runtime[100] = "Rainbow";

strcat(key_name_runtime, " Speed");

// get value via runtime string

const char *matched_key_runtime = match_key(settings, key_name_runtime);

printf("%s\n", settings[matched_key_runtime]);

// this will print "14000"

}

Use std::string instead of const char*

Another option is to just use std::strings instead. This solution “just works” as you would expect it to:

#include <iostream>

#include <map>

#include <string>

int main()

{

// create settings map

std::map<std::string, std::string> settings;

// set value via literal

char key_name_literal[100] = "Rainbow Speed";

settings[key_name_literal] = "14000";

// get value via literal

printf("%s\n", settings[key_name_literal].c_str());

// this will print "14000"

// determine runtime string

char key_name_runtime[100] = "Rainbow";

strcat(key_name_runtime, " Speed");

// get value via runtime string

printf("%s\n", settings[key_name_runtime].c_str());

// this will print "14000"

}

The reason for this is down to how std::map decides whether values for the key type are equivalent. Internally, std::map uses what’s known as a comparison object - this is basically just a class with a method that takes two values and “compares” them. The default comparison object for std::map is std::less, which defines operator(const T& lhs, const T& rhs) as return lhs < rhs;.

When two const char*s that point to different places are passed, one pointer is going to be numerically larger than the other, so the comparison object returns true, signifing that the two strings are not equivalent.

In the case of std::strings, using the < or > on two strings with identical contents will return false:

std::string a = "a";

std::string b = "a";

printf("%d\n", a == b); // prints 1

printf("%d\n", a < b); // prints 0

printf("%d\n", &a == &b); // prints 0

This means that a std::map will see the two strings as equivalent! Also of note, you can access the key comparison object using a method of std::map called std::map::key_comp.

Custom comparison object

This option expands on the idea of comparison objects by definig a custom one! There is a secret third template parameter for std::map’s constructor that allows you to pass your own comparison object. In the example below, I have created a comparison object that actually checks the contents of the string using strcmp instead of comparing them as pointers:

#include <iostream>

#include <map>

#include <string.h>

// comparison object to ensure strings with identical content are considered equal

struct compare_strings {

bool operator() (const char* lhs, const char* rhs) const

{

return strcmp(lhs, rhs);

}

};

int main()

{

// create settings map, with custom comparison object

std::map<const char*, const char*, compare_strings> settings;

// set value via literal

char key_name_literal[100] = "Rainbow Speed";

settings[key_name_literal] = "14000";

// get value via literal

printf("%s\n", settings[key_name_literal]);

// this will print "14000"

// determine runtime string

char key_name_runtime[100] = "Rainbow";

strcat(key_name_runtime, " Speed");

// get value via runtime string

printf("%s\n", settings[key_name_runtime]);

// this will print "14000"

}

I think this option is the most elegant, since it allows you to keep using const char*s and the changes needed to existing code are very minimal.

Conclusion

When I stumbled upon this issue, it puzzled me for a while since it kind of contradicted my idea of how associative arrays work. I had a hunch that it was something to do with pointers and the hashing algorithm, and being able to use Compiler Explorer to see the output of the compiler really helped me figure out what was actually going on.

This is one of those really terrible behaviours that defy people’s expectations of what something should do, and require deep knowledge of programming to understand what is actually happening. Hopefully this post will be able to help out anyone else who comes across this issue :)